Merriam-Webster describes worship as the act of showing respect and love for a god, especially by praying with other people who believe in the same god. In The Problem of Pain, C. S. Lewis expounds on the consequences (or lack thereof) of worshipping or not worshipping God: “A man can no more diminish God’s glory by refusing to worship Him than a lunatic can put out the sun by scribbling the word ‘darkness’ on the walls of his cell.” I, of course, will be examining worship in the same context as C. S. Lewis, that is, as worship of God. So, what is worship? In this essay, I will attempt to answer this question by examining worship’s object, its practicers, and its methods, both right and wrong.

To followers of Christ, the question, Whom do we worship? seems to have a terribly obvious answer. But, still, there cannot possibly come any harm from reminding ourselves that worship itself should not direct our focus earthward. We might also do well to remind ourselves that God, after all, is a jealous God and will not have us worship any other than Him:

“You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the Lord your God am a jealous God.” (Exodus 20:4–5a, ESV)

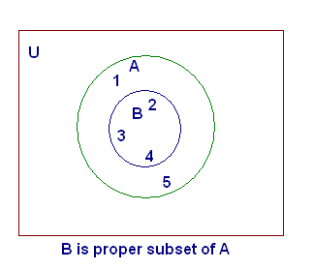

Thus, we see that worship of God and worship of idols are mutually exclusive: That is, we cannot simultaneously worship God and worship idols, whether those idols be literal carved figures or more abstract distractions like money or beauty or influence. Furthermore, we see that worship of idols does not merely diminish our worship of God but actually censures it, making it null and void, for God is jealous, and He will neither tolerate nor accept worship in which our attentions and efforts are divided.

Now that we have taken a moment to remind ourselves that the object of our worship must be only God, we must then ask: Who does the worshipping? Again, the answer seems at first painfully obvious: We, the followers of God, worship Him. But, to better understand worship, we may also the examine multiple instances in the Bible in which not only we as mortals worship God, but creation also joins with us, as well. In Psalm 66, we see this concept demonstrated:

Shout for joy to God, all the earth;

sing the glory of his name;

give to him glorious praise!

Say to God, “How awesome are your deeds!

So great is your power that your enemies come cringing to you.

All the earth worships you

and sings praises to you;

they sing praises to your name. Selah. (Psalm 66:1–4, ESV)

If we assume that the author of this Psalm has personified creation, meaning that the author has given the earth decidedly human qualities for narrative purposes, then we may view the contents of this Psalm (and others like it) as illustrations included mainly for rhetorical effect. We may also, however, consider these instances as examples of why we should be worshipping God. Romans 1:20 helps illustrates this same why, as well: “For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse” (ESV). I think we may agree that the earth is decidedly objective in its views and actions, for animals and plants (generally) at every opportunity take the courses of action that will sustain them and keep them within the pattern and order of their species and of the earth’s ecosystem as a whole. We, as human beings, are undoubtedly more intelligent than animals and plants; at least, we would like to believe so. Yet we oftentimes seem to lack that driving instinct that says to us: “This is right. This is natural. This is what we must do in order to survive.” But we are not so lost as to not be able to recognize the right thing to do when we see it. According to Paul in Romans 1:20, the correct course must be the recognition that the earth has the right idea in worshipping God. For creation is able to see that to worship God is right, that to worship God is to secure for itself protection and truth and to also bind it to a divine order and not to the destruction and chaos. We, then, must lend ourselves to the same cause in order to achieve the same results. In conclusion, I offer a part of Psalm 86 as an example of human worship:

All the nations you have made shall come

and worship before you, O Lord,

and shall glorify your name.

For you are great and do wondrous things;

you alone are God. (Psalm 86:9-10, ESV)

Now that I have defined who does the worshipping and to whom we are directing that worship, I must, of course, ask: How do we worship? You may notice that it is here that my choice of narrating mainly in the first person plural becomes most relevant because it seems that worship is often communal. Many of the Psalms appear to lead a congregation in song and, thus, become communal in their worship. Not that worship cannot be private; many of David’s Psalms seem to read as an intimate communication between he and God. But even though, in worship, it seems we use such wording as to suggest that it is only our own singular person engaging in worship (i.e., “my Redeemer,” “my Savior,” “saved a wretch like me,” etcetera), typically our worship services consist of a gathering together and an emphasis on a communal experience of worshipping God. So, for the purposes of this essay and because it is due primarily to my participation on a worship team that I am writing this essay, I will consider the kind of worship we participate in as members of the church as a mainly communal act.

Still, it seems worship may be divided into both physical and spiritual acts. I will begin with the former, that is, how we worship physically. In the book of Psalms (and other books), there are many mentions of bowing, both human and otherwise, during and as an act of worship to God (see Genesis 24, Psalm 5, 95, 138). Certainly singing and the use of musical instruments are obvious methods of worship. A famous example that we may examine as an illustration of physical worship is that of David dancing upon the return of the Ark to Jerusalem:

And David danced before the Lord with all his might. And David was wearing a linen ephod. So David and all the house of Israel brought up the ark of the Lord with shouting and with the sound of the horn. (2 Samuel 6:14-15, ESV)

Also important in this illustration is that David’s act of worship is one in which he is utterly unashamed, all inhibitions banished. In fact, even after Michal criticizes him for being so “un-kingly,” David rebukes her:

“It was before the Lord, who chose me above your father and above all his house, to appoint me as prince over Israel, the people of the Lord—and I will celebrate before the Lord. I will make myself yet more contemptible than this, and I will be abased in your eyes.” (2 Samuel 6:21-22a, ESV)

This, then, is an example of physical worship: total joyful abandonment because of the nearness of God’s presence. Since I am a member of a worship team and, of course, of the church, I may here also use the worship service as an example of how we also have an opportunity to worship in the same manner as David.

Note that I say this is one example of physical worship because it is seemingly not the only one. Surely, we may worship God in many different manners, both communally and privately, and, next, in my discussion of spiritual worship, I will further explore how all-encompassing worship seems to be in the Christian life. Thus, spiritual worship I will define as Paul speaks of it in Romans:

I appeal to you therefore, brothers, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship. Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect. (Romans 12:1-2, ESV)

Spiritual worship, then, seems similar to the commandment to have no idols. That is, if Paul here equates spiritual worship with the act of presenting ourselves as living sacrifices, this, again, leaves us with two choices: We must devote ourselves fully or not at all, because our sacrifice may not be divided. That is, we may not sacrifice an arm to this, a leg to that, an ear and a few toes to God, and expect that He will be satisfied; instead, we must sacrifice ourselves fully to one cause, to one jealous God, in order to fully engage in worship. It is also worth mentioning that, although I use the physical body as an example of how we may divide ourselves in worship, I mean to use it figuratively. In other words, we may not be divided neither in our actions nor our mentalities.

So how may we practice spiritual worship? Paul conveniently answers my question: By refusing to conform to the world and instead conforming to the model of Christ (Romans 12:2). It is also worth mentioning that to be living sacrifices (not so subtly) implies that while we are living, while we are going about our everyday lives, we are also sacrifices. So, we worship and glorify God in our everyday conduct and in the use of our talents; and, thus, many different forms of worship emerge.

As is the case with most definitions, we may further define proper worship by what it is not, and to this end, I will consider three cases of improper worship: worship of other gods, worshipping in vain, and disorderly worship. In all of these, we immediately see that none are really proper worship at all. The first, worship of other gods, we have already touched upon multiple times, and since the discussion has been as such, I will quote only Luke 4:8, where Jesus is tempted by Satan in the desert: “And Jesus answered him, ‘It is written, “You shall worship the Lord your God, and him only shall you serve”’” (ESV).

Worshipping in vain appears to be similar and is addressed by Jesus in Mark 7:

And the Pharisees and the scribes asked him, “Why do your disciples not walk according to the tradition of the elders, but eat with defiled hands?” And he said to them, “Well did Isaiah prophesy of you hypocrites, as it is written,

‘This people honors me with their lips,

but their heart is far from me;

in vain do they worship me,

teaching as doctrines the commandments of men.’

You leave the commandment of God and hold to the tradition of men.”

And he said to them, “You have a fine way of rejecting the commandment of God in order to establish your tradition!” (Mark 7:5-9, ESV)

What Jesus appears to be addressing here, then, is the vanity of worshipping God without obeying him, or even replacing his commandments with one’s own prerogatives. For what good is it to sing or to speak or act in praise of God, when we have not surrendered to Him? This, again, seems to hearken back to having no other idols. To worship God without obedience, then, is to make an idol out of our own will and, thus, divide ourselves in our act of worship, which, as we already know, voids the act altogether.

Finally, I will consider disorderly worship; or, rather, I will allow Paul, who writes the following in his second letter to the Corinthians, to consider it for me:

What then, brothers? When you come together, each one has a hymn, a lesson, a revelation, a tongue, or an interpretation. Let all things be done for building up. If any speak in a tongue, let there be only two or at most three, and each in turn, and let someone interpret. But if there is no one to interpret, let each of them keep silent in church and speak to himself and to God. Let two or three prophets speak, and let the others weigh what is said. If a revelation is made to another sitting there, let the first be silent. For you can all prophesy one by one, so that all may learn and all be encouraged, and the spirits of prophets are subject to prophets. For God is not a God of confusion but of peace. (2 Corinthians 14:16-33, ESV)

Again, I am reminded of creation worshipping God, of adhering to an order it cannot help but recognize as right and divine. So must we be orderly in what we do in worship. Without a semblance of order, our communal act crumbles because each is seeking not to edify God and the members of the church, but to edify him or herself. To worship in a disorderly manner, then, is not to worship at all.

In all of these cases, we may see that improper worship yields the same result: It becomes unacceptable to God. And while I do not believe that we should define worship only by what it is not, I think it important to consider how we may be tempted to transgress.

As I come to the end of this essay, I now ask myself why? Why do we worship God? It is clear to me from this exploration that worship and its characteristics are clearly defined in the Bible, and anything less ceases to be worship at all. So, it seems we as humans have a choice: To worship God or to refuse to worship Him. However, here I will remind you of the quote from C. S. Lewis that I began with: “A man can no more diminish God’s glory by refusing to worship Him than a lunatic can put out the sun by scribbling the word ‘darkness’ on the walls of his cell.” Regardless of whether we worship him or not, God is God; and, as is stated in Romans 14, one day every knee will bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord. So, even if we do not acknowledge that God is worthy of our worship now, one day, we must. And, as for me, I would rather commit my worship willingly.

As human, we are also the crowning achievement of God’s creation, made in His own image, the fingerprint of the Divine on the imperfect. Above all else, He loves us, and I find no better explanation. For if I am to worship something, someone, I can find none greater, none more worthy, than the Alpha and Omega, the beginning and the end, my Redeemer and my only hope for Salvation.

Finally, as Christians, worship is a matter of devoting ourselves fully to Him. Here, I feel I must mention that this concept of worship appears to be much more important and much more encompassing than merely conducting or participating in a worship service on Sunday. And it is. In other words, a worship service should not be the only act of worship we have in our lives; in fact, if it were, by the concepts we’ve delineated above, it is unacceptable. Because to worship God only for thirty minutes on Sunday mornings is not to worship Him at all. Neither do I mean to imply by this statement that we should not have worship services. I think David’s example of worship is a fantastic one, an example that clearly shows that music, that singing and dancing and whatever else is clearly glorifying and welcome in God’s eyes. If worship is a diamond, it seems that Sunday worship should be is a facet of that gem, a shining, brilliant, facet—but a part of a whole, all the same.